Distributed noise addition and infinite divisibility

Differentially private mechanisms often require their implementions to be distributed across multiple parties. One common case is when multiple parties only add a portion of the noise, such that the total noise in the final output is achieved by summing up the noise across multiple parties

This kind of distributed noise addition is used in federated learning protocols like Secure Aggregation, or in contexts like multi-message shuffle protocols (e.g. Balle et al. 2020, Ghazi et al. 2021).

A simplified setting we’ll study in this post is the following:

- There are $n$ parties participating in the protocol, each adding some iid random variable to the resulting measurement

- We want to analyze the sum of the total noise across parties and we’ll look at cases where only a $\beta = m/n$ (for $m \le n$) fraction of parties add noise, either due to dropout or maliciousness.

- In some cases we might look at cases where more than $n$ parties participate, i.e. $\beta > 1$.

Infinite divisibility

The primary tool in our toolbox for mechanism design here is the notion of infinitely divisible probability distributions.

Definition 1: A probability distribution $F$ is infinitely divisible if, for every positive integer $n$, there exists $n$ iid random variables $X_i$ such that $F \sim \sum_{i=1}^n X_i$. Furthermore, $F$ is self-decomposable if it is infinitely divisible and each $X_i$ follows an identical identical distribution family as $F$, just with different shape parameters.

As long as the total noise we want to add is from an infinitely divisible distribution $F$, we can easily split up the noise across $n$ parties who will just sampling from their individual $X_i$ portion.

To handle $\beta$ honest fraction of parties, we will typically try to leverage a distribution that is self-decomposable, so the noise under a $\beta$ fraction is still guaranteed to follow the same distribution family as if all parties added noise. This will make analysis much easier, as often our privacy analyses extend naturally as a distribution’s shape parameters change.

Gaussian noise

We’ll start with an easy warm-up. The most famous infinite divisible and self decomposable distribution is the gaussian.

\[\mathcal{N}(\mu, \sigma^2) = \sum_{i=1}^n \mathcal{N}\left(\frac{\mu}{n}, \frac{\sigma^2}{n}\right)\]We’ll analyze privacy under $\rho$-zCDP, assuming our measurement has $\Delta_2$ sensitivity. From Bun & Steinke 2016 Proposition 1.6, we know that additive gaussian noise satisfies $\frac{\Delta_2^2}{2 \sigma^2}$-zCDP. Therefore:

- Each of the $n$ parties should add $\mathcal{N}\left(0, \frac{\sigma^2}{n}\right)$ element-wise noise to their measurement

- If only $\beta$ fraction of parties can be guaranteed to add noise, we should satisfy $\frac{\Delta_2^2}{2 \beta \sigma^2}$-zCDP.

One challenge with using continuous distributions here is that practical mechanisms are implemented on finite computers. This poses challenges (e.g. the classic Mironov (2012)1) even if a single party is adding noise. Multiple parties only amplifies the challenges here, as approximations or errors in each $X_i$ will accumulate in the final sum.

Discrete gaussian noise

It is tempting to hope that the discrete gaussian introduced by Canonne et al. 2020 (and used in the 2020 US Census release) is infinitely divisible, and can be used to mitigate some of the complications of the continuous gaussion. Unfortunately it is not the case, although sums of discrete gaussians are very close to gaussian! See the follow-up paper from Kairouz et al. 2021 for the full analysis and utility in the federated learning regime.

While the discrete gaussian still performs well in the distributed noise addition setting, the fact that it is not infinitely divisible makes it a little clunky to use.

Skellam noise

Skellam noise was considered as an alternative to gaussian noise (and even discrete gaussian noise) for discrete outputs in Agarwal et al. 2021. A skellam random variable is the difference of two independent poisson random variables, making it easy to sample from:

\[Skel(\lambda_1, \lambda_2) = Poi(\lambda_1) - Poi(\lambda_2)\]For our purposes we will just parameterize the Skellam distribution with a single $\lambda$, $Skel(\lambda) = Poi(\lambda/2) - Poi(\lambda/2)$ and consider the additive 0-mean distribution. Infinite divisibility of the Skellam distribution follows from infinite divisibility of the Poisson distribution:

\[Poi(\lambda) = \sum_{i=1}^n Poi(\lambda / n)\]Therefore:

\[\begin{align*} Skel(\lambda) &= Poi\left(\frac{\lambda}{2}\right) - Poi\left(\frac{\lambda}{2}\right)\\ &= \sum_{i=1}^n Poi\left(\frac{\lambda}{2 n}\right) - \sum_{i=1}^n Poi\left(\frac{\lambda}{2 n}\right)\\ &= \sum_{i=1}^n Skel(\lambda / n) \end{align*}\]Agarwal et al. (Corollary 3.6) showed that adding $Skel(\lambda)$ distributed noise to a measurement with $\ell_1$ and $\ell_2$ sensitivity $\Delta_1$ and $\Delta_2$ achieves Renyi differential privacy (Mironov 2017).

\[\epsilon(\alpha) \le \frac{\alpha \Delta_2^2}{2 \lambda} + \min{\left(\frac{(2\alpha - 1)\Delta_2^2 + 6\Delta_1}{4 \lambda^2} ,\frac{3 \Delta_1}{2 \lambda} \right)}\]For $\alpha > 1$ and $\alpha \in \mathbb{Z}$. This bound comes close to the gaussian, as the first term is identical to the RDP bound for $\mathcal{N}(0, \lambda)$.

For only a $\beta$ honest subset, the final disitribution is $Skel\left(\beta\ \lambda\right)$.

Discrete laplace noise

We’ve shown cases of distributed noise addition satisfying zCDP and RDP. What about Pure DP? One fact that can help us is that the difference of two geometric random variables is discrete laplacian:

\[DLap(a) = Geo(1-e^a) - Geo(1-e^a)\]We can show this is true via looking at the characteristic function $\varphi$ for the geometric distribution:

\[\begin{align*} \varphi_{Geo(p)}(t) &= \frac{p}{1 - e^{i t} (1 - p)}\\ \varphi_{-Geo(p)}(t) &= \frac{p}{1 - e^{-i t} (1 - p)}\\ \varphi_{Geo(1-e^a) - Geo(1-e^a)}(t) &= \frac{(1-e^a)^2}{\left(1 - e^{i t} e^a\right)\left(1 - e^{-i t} e^a\right)}\\ &= \frac{cosh(a)-1}{cosh(a)-cosh(i t)}\\ &= \frac{tanh(a/2)sinh(a)}{cosh(a)-cosh(t)} \end{align*}\]This exactly matches the discrete laplace’s characteristic function (which is equal to its MGF) see e.g. the scipy docs.

How does this help us? Well, it turns out that the geometric distribution (as a limiting case of the negative binomial2 distribution) is infinitely divisible!

\[Geo(p) = NBinom(1, p) = \sum_{i=1}^n NBinom(1/n, p)\]With this in hand, we can ensure discrete laplace noise by having each party sample noise according to $X_i \sim NBinom(1/n, p) - NBinom(1/n, p)$:

\[\begin{align*} DLap(a) &= Geo(1-e^a) - Geo(1-e^a)\\ &= \sum_{i=1}^n NBinom(1/n, p) - \sum_{i=1}^n NBinom(1/n, p)\\ &= \sum_{i=1}^n (NBinom(1/n, p) - NBinom(1/n, p)) \end{align*}\]This approach is outlined in Balle et al 2020 in the context of multi-message shuffle protocols.

One question we haven’t answered is what happens if we can only guarantee a $\beta = \frac{m}{n}$ fraction of parties honestly add noise here? In this case, we will have:

\[Z_m = \sum_{i=1}^m NBinom(1/n, p) - NBinom(1/n, p) = NBinom(\beta, p) - NBinom(\beta, p)\]Unfortunately $Z_m$ is not the same as a standard discrete laplace distribution! We run into this problem because the discrete laplace distribution is not self decomposable. In fact, I am not sure $Z_m$ has been studied rigorously in the privacy literature at all (but someone let me know if I’m wrong)! Let’s study it ourselves.

The generalized discrete laplace: a self-decomposable analog of the laplace mechanism

I found that the general case of the difference of independent negative binomials has been analyzed, e.g. in Lekshmi & Sebastian 2014 under the name “Generalized Discrete Laplace” or GDL. Let’s call a mechanism using GDL additive noise the GDL mechanism:

\[GDL(\beta, a) = NBinom(\beta, 1 - e^{-a}) - NBinom(\beta, 1 - e^{-a})\]The generalized discrete laplace is self-decomposable, from the self-decomposability of the negative binomial.

\[\begin{align*} \sum_{i=1}^n GDL(\beta, a) &= \sum_{i=1}^n NBinom(\beta, 1 - e^{-a}) - NBinom(\beta, 1 - e^{-a})\\ &= \sum_{i=1}^n NBinom(\beta, 1 - e^{-a}) - \sum_{i=1}^n NBinom(\beta, 1 - e^{-a})\\ &= NBinom(n\beta, 1 - e^{-a}) - NBinom(n\beta, 1 - e^{-a})\\ &= GDL(n\beta, a) \end{align*}\]Let’s see what this bad boy looks like numerically via convolving two negative binomials:

Surprisingly, it seems like (from staring at the plots) that if only $\beta$ fraction of parties add noise, we see higher variance (with similar tail behavior) vs scaling $\epsilon’ = \epsilon/\beta$ under the discrete laplace. Maybe that means it has better privacy, formally?

Let’s try to show something about the privacy loss under this mechanism.

Theorem 1: The univariate GDL mechanism with $\Delta \in \mathbb{N}$ sensitivity satisfies differential privacy with

\[\epsilon \le \begin{cases} a \Delta + \log \frac {\sideset{_2}{_1}F[\beta; \beta; 1; e^{-2a}]} {\sideset{_2}{_1}F[\beta; \beta + \Delta; 1 +\Delta ; e^{-2a}]} \frac{\Gamma(\Delta+1)\Gamma(\beta)}{\Gamma(\beta + \Delta)} &\text{ if 0 < $\beta \le 1$}\\ a \Delta & \text{ if $\beta > 1$} \end{cases}\]Where $\sideset{_2}{_1}F$ is the hypergeometric function and $\Gamma$ is the gamma function.

The $\beta > 1$ case is trivial3, since we know that $\beta = 1$ recovers the discrete laplace exactly. For the $0 \lt \beta \le 1$ we’ll start off with the PMF of the GDL in terms of hypergeometric functions (Lekshmi & Sebastian eq 2.5):

\[Pr[GDL(\beta, a) = x] = e^{-a|x|}(1-e^{-a})^{2\beta}\ \sideset{_2}{_1}F[\beta; \beta + |x|; |x| + 1; e^{-2a}]\ \frac{\Gamma(\beta + |x|)}{\Gamma(|x| + 1)\Gamma(\beta)}\]We also make use of the following identity the DLMF eq 15.2.2 :

\[\begin{align*} \sideset{_2}{_1}F[a; b; c; z] &= \frac{\Gamma(c)}{\Gamma(a)\Gamma(b)} \sum_{s=0}^\infty \frac{\Gamma(a+s)\Gamma(b+s)}{\Gamma(c+s)s!}z^s \end{align*}\]Without loss of generality, consider the neighboring datasets at points $\mu_D=\Delta$ and $\mu_{D’} = 0$:

\[\begin{align*} \log \frac{Pr[\Delta + GDL_{\beta, a} = k]}{Pr[0 + GDL_{\beta, a} = k]} &= \log \frac{Pr[GDL_{\beta, a} = k-\Delta]}{Pr[GDL_{\beta, a} = k]}\\ &= \log \frac {e^{-a|k - \Delta|} \sideset{_2}{_1}F[\beta; \beta + |k - \Delta|; |k - \Delta| + 1; e^{-2a}]} {e^{-a|k|} \sideset{_2}{_1}F[\beta; \beta + |k|; |k| + 1; e^{-2a}]} \frac{\Gamma(|k|+1)\Gamma(\beta + |k-\Delta|)}{\Gamma(|k-\Delta| + 1)\Gamma(\beta + |k|)} \\\\ &= a(|k|-|k-\Delta|) + \log \left(\frac{\sideset{_2}{_1}F[\beta; \beta + |k - \Delta|; |k - \Delta| + 1; e^{-2a}]} {\sideset{_2}{_1}F[\beta; \beta + |k|; |k| + 1; e^{-2a}]}\right) + \log \left(\frac{\Gamma(|k|+1)\Gamma(\beta + |k-\Delta|)} {\Gamma(|k- \Delta| + 1)\Gamma(\beta + |k|)}\right)\\\\ &= a(|k|-|k-\Delta|) + \log \frac{\frac{\Gamma(1 + |k-\Delta|)}{\Gamma(\beta)\Gamma(\beta + |k-\Delta|)}} {\frac{\Gamma(1 + |k|)}{\Gamma(\beta)\Gamma(\beta + |k|)}} \frac{\sum_{s=0}^\infty \frac{\Gamma(\beta+s)\Gamma(\beta + |k-\Delta| +s)}{\Gamma(1 + |k-\Delta|+s)s!}e^{-2 a s}} {\sum_{s=0}^\infty \frac{\Gamma(\beta+s)\Gamma(\beta + |k| +s)}{\Gamma(1 + |k| +s)s!}e^{-2 a s}} + \log \left(\frac{\Gamma(|k|+1)\Gamma(\beta + |k-\Delta|)} {\Gamma(|k- \Delta| + 1)\Gamma(\beta + |k|)}\right)\\\\ &= a(|k|-|k-\Delta|) + \log \left( \frac{\Gamma(1 + |k- \Delta|)\Gamma(\beta + |k|)} {\Gamma(1 + |k|)\Gamma(\beta + |k-\Delta|)} \frac{\sum_{s=0}^\infty \frac{\Gamma(\beta+s)\Gamma(\beta + |k-\Delta| +s)}{\Gamma(1 + |k-\Delta|+s)s!}e^{-2 a s}} {\sum_{s=0}^\infty \frac{\Gamma(\beta+s)\Gamma(\beta + |k| +s)}{\Gamma(1 + |k| +s)s!}e^{-2 a s}} \right) + \log \left(\frac{\Gamma(|k|+1)\Gamma(\beta + |k-\Delta|)} {\Gamma(|k- \Delta| + 1)\Gamma(\beta + |k|)}\right)\\\\ &= a(|k|-|k-\Delta|) +\log \frac{\sum_{s=0}^\infty \frac{\Gamma(\beta+s)\Gamma(\beta + |k-\Delta| +s)}{\Gamma(1 + |k-\Delta|+s)s!}e^{-2 a s}} {\sum_{s=0}^\infty \frac{\Gamma(\beta+s)\Gamma(\beta + |k| +s)}{\Gamma(1 + |k| +s)s!}e^{-2 a s}}\\ &= A + B \end{align*}\]We will proceed by showing that $k = \Delta$ maximizes this quantity, and the theorem statement follows directly from plugging in $\Delta$ for $k$ above.

Clearly, $A$ is maximized (with value $a \Delta$) when $k \ge \Delta$, so it suffices to show $B$ is maximized at $k = \Delta$. Informally, $B$ smoothly interpolates between $0$ and $C = \log \left(\frac{\Gamma(|k|+1)\Gamma(\beta + |k-\Delta|)}{\Gamma(|k- \Delta| + 1)\Gamma(\beta + |k|)}\right)$ as a function of $a$.

Here are the endpoints:

\[\begin{align*} \lim_{a \to \infty} B &= \log \frac{\sideset{_2}{_1}F[\beta; \beta + |k-\Delta|; 1 + |k-\Delta|; 0]} {\sideset{_2}{_1}F[\beta; \beta + |k|; 1 + |k|; 0]} - \log \left( \frac{\Gamma(1 + |k- \Delta|)\Gamma(\beta + |k|)} {\Gamma(1 + |k|)\Gamma(\beta + |k-\Delta|)}\right) \\ &= \log\left(\frac{1}{1}\right) + C = C\\ \lim_{a \to 0} B &= \lim_{a \to 0} \frac{\sum_{s=0}^\infty \frac{\Gamma(\beta+s)\Gamma(\beta + |k-\Delta| +s)}{\Gamma(1 + |k-\Delta|+s)s!}e^{-2 a s}} {\sum_{s=0}^\infty \frac{\Gamma(\beta+s)\Gamma(\beta + |k| +s)}{\Gamma(1 + |k| +s)s!}e^{-2 a s}}\\ &= 0 \end{align*}\]We do know $C$ is maximized at $k=\Delta$ (see this stackexchange post). We could stop there and say $\epsilon \le a \Delta + C$, but this would not be tight. However, we can use a similar approach to show that the quantity $f(x) = \sum_{s=0}^\infty \frac{\Gamma(\beta+s)\Gamma(\beta + |x| +s)}{\Gamma(1 + |x| + s)s!}e^{-2 a s}$ has a single maximum when $x = 0$. Informally4, the result follows from:

- Noticing for $B = \frac{f(k-\Delta)}{f(k)}$, the numerator and denominator of are translations of each other.

- $f(-x) = f(x)$

- $f$ is maximized at 0, and is convex and decreasing on the interval $[0, \infty)$.

Therefore $\frac{f(x)}{f(x + \Delta)} \le \frac{f(0)}{f(\Delta)}$.

To check that the bound is tight for $\beta \le 1$, we can check it vs. numerical approaches with Google’s DP accounting library, where $a = \frac{\epsilon_0}{\Delta}$.

These plots align with the PMF plots above in that we do see improved privacy over the baseline $\epsilon_0/\beta$ in the $\Delta=1$ regime. Interestingly, this is not universal across all $\Delta$ regimes.

Fun facts on the GDL distribution:

- As $\beta \gg 1$, the GDL distribution will approach the gaussian via the central limit theorem. As such, the GDL may be parameterized to enjoy gaussian-like approximate DP guarantees while simultaneously satisfying pure DP.

- As $a \to \infty$ (and therefore $p \to 1$), the negative binomial approaches the poisson distribution. This means that the GDL actually approaches the skellam distribution for large values of $a$! To make this parameterization private requires $\beta \gg 1$. Quantifying this convergence would be an interesting follow-up question.

- For some parameterizations, the hypergeometric term in the theorem statement is very small. The bound can be simplified by taking a looser upper bound without its small (negative) contribution.

- It should be relatively straightforward to translate univariate bounds to multivariate bounds similar to the laplace mechanism.

Positive-only noise addition: negative binomial mechanism

In some distributed noise addition settings, we may be constrained such that each party can only add positive noise, which forbids all of the above mechanisms which are symmetric. This setting has come up in the literature in e.g. one of the shuffle mechanims of Ghazi et al 2020.

There are two major challenges with this setting:

- We need to move away from pure DP or divergence-based privacy notions (Renyi DP, zCDP). The privacy notion we can show is approximate $(\epsilon, \delta)$-DP. The reason is outlined in this stackexchange post.

- Usually, when restricted to positive-only noise, one typical move is to use $\tau$-truncated symmetric noise distribution, whose mean is centered at $\tau$ (meaning its support is on $[0, 2\tau]). This is explored a bit in the stackexchange link above. However, all infinitely divisible distributions (other than the one point distribution) must have non-bounded support, excluding truncated mechanisms.

In the discrete setting, the natural distribution to sample from is again the negative binomial (of which the Poisson is a limiting case). The Ghazi et al. paper (Theorem 13) show that the negative binomial mechanism with sensitivity $\Delta \in \mathbb{N}$ satisfies approximate DP for some specific parameterizations.

A fascinating result they prove in this setting (Lemma 15) is that the MSE of any infinitely distributed, non-negative discrete mechanism must be at least $\Omega_{\epsilon}(\log 1/\delta)$! That is, we have a formal separation between this setting and the standard central summation setting. We can use some numerical privacy analysis to show that the mean of the negative binomial mechanism does not fall below $\log 1/\delta$ for any value of $\epsilon$.

Concluding thoughts

Distributed noise addition comes up pretty often in private system design, across both the central and shuffle models of privacy. Hopefully this post provided a good introduction to this interesting setting.

To summarize, we outlined a few techniques spanning multiple privacy notions (pure DP, Renyi DP, zCDP, and approximate DP) and settings (non-negative noise, discrete / continuous noise). In each case, we exploited infinite divisibility and self-decomposability to analyze privacy under a varying fraction of participating parties. The colab generating plots can be found here.

There are a few things we did not explore:

- The continuous analog to the GDL we explored is the difference of Gamma random variables. In the limiting case where the Gamma RVs are exponential, this yields the continous laplace distribution. Does the so-called Generalized Continous Laplace (GCL?) satisfy Pure DP? (See update

- There are a number of continous infinitely divisible distributions like like the Cauchy (see Nissim et al. 2007) or Student’s T distribution (see Bun & Steinke 2019) are used when scaling noise by smooth sensitivity of the measurement rather than the global sensitivity5. For an overview of this approach, see section 3.1 of The Complexity of Differential Privacy by Vadhan. Given that smooth sensitivity is computed per dataset, it seems especially challenging to use in the distributed setting e.g. if no party can see the whole dataset!

- Under cryptographic multi-party computation (MPC) protocols, it is possible for parties to jointly sample noise distributed according to more distributions than just infinitely divisible ones. The main tool this setting typically leverages is interaction between the parties. For the approaches outlined in this post, the parties can sample noise independently without any interaction (which can also be a component MPC protocols, to be clear). See e.g. Keller et al 2023 for an example, which outlines protocols for many of the distributions we explored here.

Update Aug 22, 2024: The Arete distribution and the GDL in the low-privacy regime

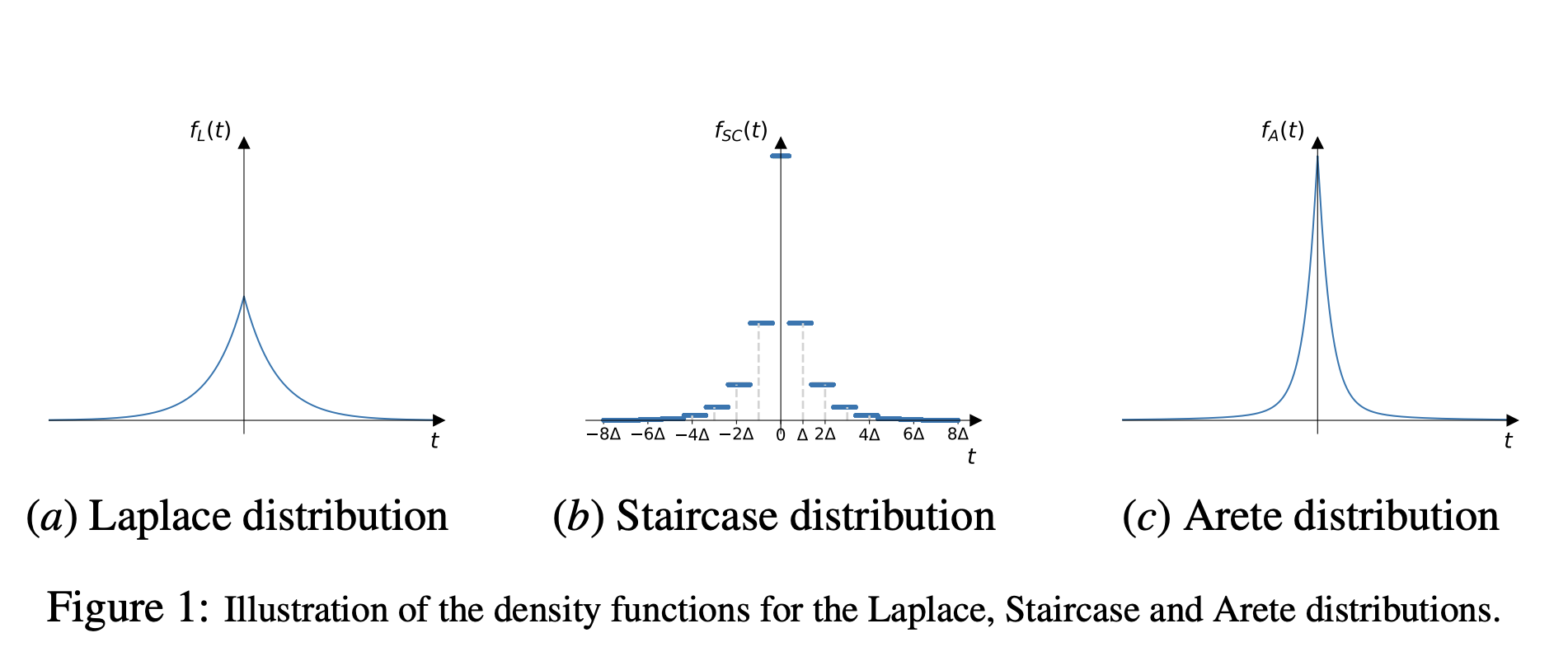

Pagh & Stausholm 2022 came up with a very interesting infinitely divisible distribution to improve pure DP performance in the low-privacy regime ($\epsilon \gg 1$): the Arete distribution. Here’s a figure from the paper comparing its density to the Laplace and staircase distribution (see Geng et al 2012, Geng et al 2015):

The staircase mechanism outperforms the laplace mechanism in the low privacy regime, and the motivation behind the Arete distribution is to match some of the performance characteristics of the staircase mechanism. It can be defined as:

\[Z = X_1 - X_2 + Y\]Where $X_1, X_2 \sim \Gamma(\alpha, \theta)$ and $Y ~ Laplace(\lambda)$. It turns out that just sampling from the difference of $\Gamma$ distributions cannot be private when $\alpha < 1$, since there is a singulary at 0. The authors smooth out this singularity by adding Laplace noise (which itself is infinitely divisible). Note that while the Arete distribution is infinitely divisible, it is not self-decomposable.

Studying the Arete distribution though, I wonder if the GDL with $\beta < 1$ actually has properties similar to the staircase mechanism for $\epsilon \gg 1$ and $\Delta > 1$?6 One quick thing we can check is whether it has exponentially decreasing variance with epsilon. The staircase mechanism has variance $O(e^{-2 \epsilon / 3})$, whereas the Discrete Laplace with large $\Delta$ has variance approximately $O(1/\epsilon^2)$.

The above plot optimizes7 the GDL for variance for a given level of $\epsilon$. As you can see, we do see an exponential relationship with $\epsilon$ in the low privacy ($\epsilon > 10$) regime! In the medium/high privacy regime, the discrete laplace is still optimal, and the GDL just uses $\beta = 1$.

I’ve also plotted variance from the continuous and discrete staircase mechanism. The GDL appears to have the same asymptotic behavior ($O(e^{-\epsilon})$) as the discrete staircase (off by about a constant factor of 4). This was a pleasant surprise showcasing yet more versatility of the GDL mechanism!

-

I feel like I cite this paper every other post :D ↩

-

Note that the generalized negative binomial whose stopping time parameter is a real number is often refered to as the Polya distribution, but in this post we just match what scipy does 😂. ↩

-

I believe this is tight under pure DP, but it should be possible to show approximate / Renyi DP since the distribution will approach the gaussian as $\beta \gg 1$. ↩

-

This is kind of handwavy, so consider this a TODO to improve the proof :) ↩

-

This is a similar approach to the one we explored in the previous post on privately bounding local sensitivity. ↩

-

It is known that the optimal staircase mechanism in the discrete setting with $\Delta=1$ is the discrete laplace, so we need to look at $\Delta>1$ to find better mechanisms. ↩

-

I numerically searched for values of $a$ and $\beta$ that minimizes variance subject to the privacy constraint. ↩